Taste

How discerning can be deceiving

What’s one of your favorite videos to revisit? You know—one of those videos that you found years ago and somehow still find yourself returning to over and over again, often when you need it most? This two minute, beautifully typeset excerpt from an NPR interview with Ira Glass is one of those favorites for me. He’s talking about storytelling, but points out that his message applies to anyone doing creative work.

I love how he succinctly describes the struggle and frustration of making things that we know just aren’t good enough—the gap—and goes on to make the connection to a seemingly innocuous idea: taste. “Your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you’re making, is kind of a disappointment to you.” By the time most of us decide to put in the effort to make something in a creative field—be it music, art, writing, or even code—it’s practically inevitable that we’ve already become attuned to sniff out the good from the bad, the insightful from the insipid, and the spontaneous from the sloppy. We’re constantly exposed to other people’s creative output, it’s only natural that we develop our taste, our sense for what we like and dislike, in the process. But, does that mean we’re doomed to a lifetime of constant disappointment?

I like food a lot, but I dislike being called a foodie almost as strongly. I’ll often catch myself describing a recent memorable meal to a friend, like how the roasted potatoes with one of the entrées at Zuni Cafe were some of the potatoiest [sic] potatoes I’d ever tasted, and my captive companion will remark, “Oh! So you must be a really big foodie then?” I hesitate, laugh sheepishly, mumble something about trying to appreciate food, and usually clumsily settle on a reluctant “so… yeah, I guess you could say I’m a foodie.”

Foodies love food. I love food. And if that’s all the association evoked, then I would happily embrace it. But when I think of a “foodie”, I also think of hypercritical Yelp reviews, the stressful fixation on only finding the best X, Y, Z, and generally being “that person” among a group of friends who always has an extremely difficult time enjoying the food at most places. (Me: “No! Wait! There’s another place 0.7 miles from here that’s rated a half star higher!” Group: collective groan). Sometimes I wonder if some foodies actually enjoy eating anymore, especially without the badge of a #1 spot on a blog’s list, 3 Michelin stars, or 5 / 5 on Yelp.

I dislike being called a foodie because I think we associate the word with more than just enjoying and tasting food. We associate being a foodie with judging food: deciding the good from the bad, writing a review, giving a score, and generally somehow always miraculously finding a way to be dissatisfied with any meal, from Popeye’s to pop-up. Sufficiently refined taste can always find a flaw. There’s a fine line between appreciating something and judging whether or not that something is “good enough”, and in fact they often feed into each other. Learning something new about tasting food, like how to pay attention to textural contrast, can easily become yet another way to be disappointed. When Ira Glass talks about taste and the gap it creates, he’s focusing on how taste easily turns into judgement, which turns into disappointment and frustration.

Thanks to sheltering-in-place, I’ve been making a lot of espresso at home. The experience so far, in addition to keeping me more than adequately caffeinated, has helped me appreciate (and miss) coffee shops and baristas even more: making good espresso is hard. The sheer number of variables affecting a shot of espresso is overwhelming: choice of beans (including their origin and roast level), choice of equipment (e.g. espresso machine, grinder), dose (how much coffee to use), grind fineness, puck preparation (e.g. distribution, tamping), brew temperature, brew pressure, brew ratio (how much water to pull as output), extraction time and more. To add to the fun: small adjustments, like pulling a 36 gram shot instead of 34 grams, can often lead to wild differences in how the final shot tastes. Next time you sip a delicious latte from your local coffee shop, consider tipping generously—it wasn’t easy!

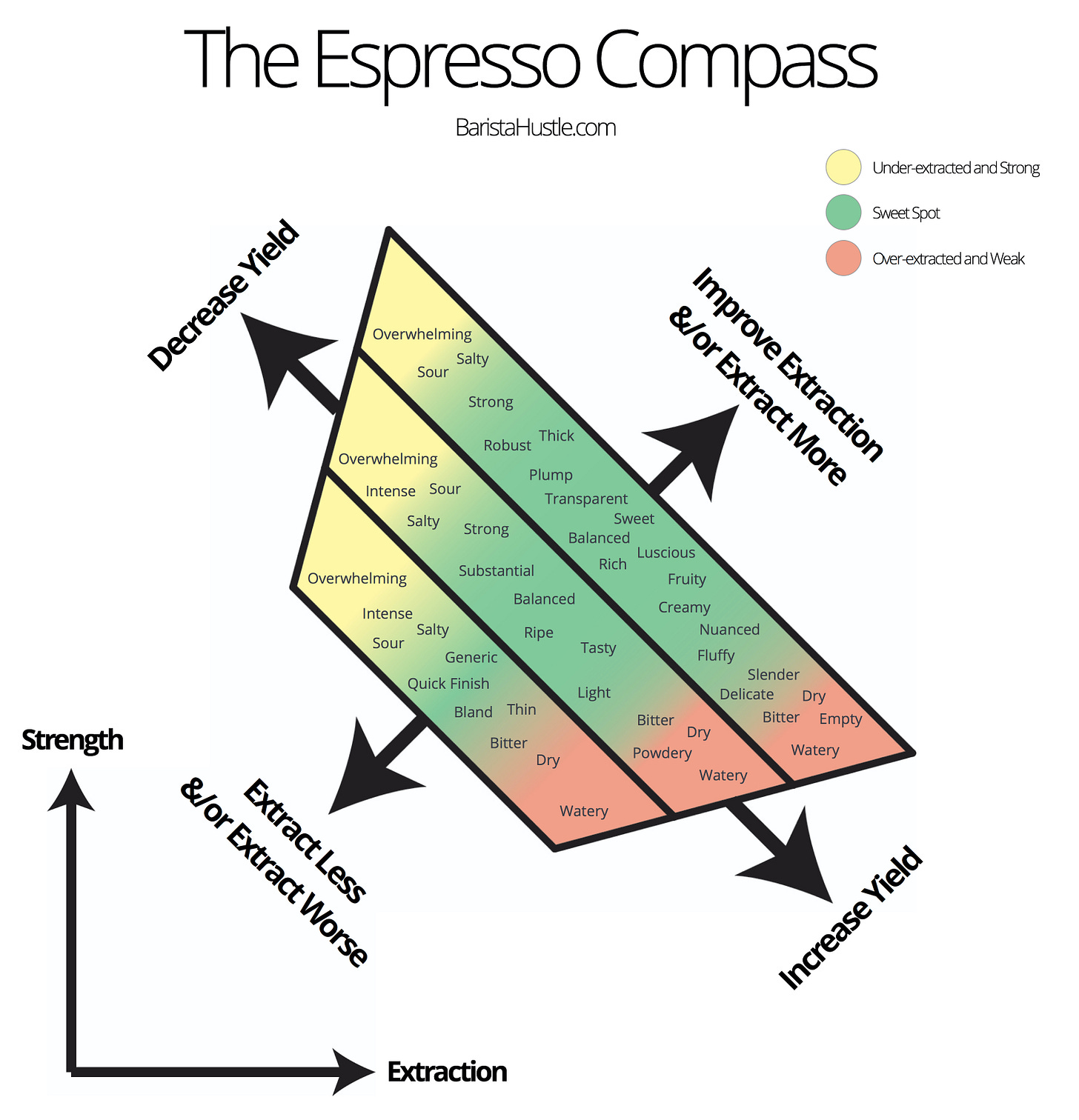

I’ve made a few very nice shots, and many more nearly undrinkable ones along the way. Each time, it’s all too easy to immediately taste, or rather judge, whether or not the shot is “good enough” and feel a little disappointed when inevitably it isn’t. Sadly, disappointment doesn’t magically make espresso taste better (if only). But then, how do I improve? I still need to taste each shot, but instead of beating myself up, I try to focus on observing—gathering data. What do I notice? What words would I use to describe it? What can I learn for next time? One of my favorite coffee blogs, Barista Hustle, has an Espresso Compass that maps different taste descriptors like “sour”, “bitter”, and “dry” and suggests parameters to tweak based on where you land. As with many graphs, the goal is to move up and to the right.

Judgement is one-dimensional: bad to good. By stepping past it, I can turn my sense of taste from an overly simple source of frustration into a powerful GPS for navigating a complex process. Thanks to this compass, I can not only see a literal “gap” in taste, but I can start to understand what it means. Each shot of espresso is another step, another jolt of caffeine, and each taste gives another glance toward how to improve the next one, up and to the right, toward narrowing the gap.

As a child, I was once talking to my father about cooking when he casually but completely seriously said that “the essence of cooking is knowing how salty salt is.” I think I laughed at the time, but, like with many of the things my parents have taught me, the wisdom of what he said would take many years for me to internalize. When we hear noisy traffic while we’re speaking, we intuitively know how much to raise our voices to be heard. When something is in our way on the sidewalk, we know how far to step to the side. So when I taste something that’s just a little bland, do I know how much salt to add? Or will I be too caught up in disliking the food to bother noticing the reason, let alone adjust it?

We’re all constantly judging. Food, drink, music, videos, writing, each other, ourselves, practically anything that occupies our attention comes automatically with a sense for whether or not we like it: 4.5 stars, Would not recommend, Like, B-, Best Ever. But when the black-and-white lens of judgement is how we see the world, we’re limited in how much we can enjoy the things we like, and often frustrated by the things we don’t. Taste and judgement are intertwined, but not inseparable. The next time you experience something or make something that strikes you as particularly “good” or “bad”, take a moment and see how much you can unfold that knee-jerk grayscale judgement into all of its curious colors and shades. What do you notice?